It is difficult to say where the novel can be traced to or even what a novel is. There have been those to set rigid bounds to the concept and its roots, and claim its first existence to have come into being in the early 18th century. There are others who find enormous parallels to far earlier works such as epistles and the novellas. All this can be attributed to its loose definition; a fictitious prose narrative of considerable length and complexity, portraying characters and usually presenting a sequential organization of action and scenes.

A few words stand out for us immediately. First and foremost, a novel must be a work of fiction, not to imply of course that it cannot contain elements of truth or real life to the characters or story line. The second is that the work must contain a narrative, which entails both character and plot development. What differentiates a novel from other types of work, however, is the third feature, being its length and complexity.

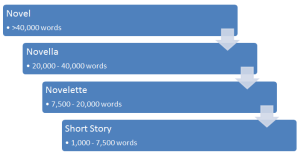

There have been attempts to split type of work by word count, as can be seen by the diagram above. Not only is this a very subjective approach to differentiation, but it also makes the mistaken assumption that word count correlates positively with a work’s level of complexity. If length alone was the answer, then why is Amadis of Gaul or the Chronicles of Arthur overlooked as novels? The answer will appear brazen to many scholars of literature, running the risk of crossing a very delicate, fine line. Chronicles, like Amadis of Gaul, are works of art, but nonetheless literature that follow a very linear timeline, and rather than being created for the purpose of developing the character, are created for the purpose of creating that character’s history. Much like biographies, chronicles, for whatever message the author sought to convey, outlines the life of one main character with sole reference to action. Thoughts matter little in chronicles, and the readers, for the most part, must do a lot of their own personal reflection to add the “human” element into the story. With the advent of the early 16th century, the first noted novel, “La Celestina” was published by Fernando de Rojas, and though structured much like a play through a series of dialogues, there was something remarkably different about this genuine pioneer of literature. Relative to chronicles and the novels that would follow, this work was incredibly short and yet it had the necessary length to dive deeply into the lives of several people and display their thoughts, emotions and the actions that were consequential thereof. A literary revolution away from solely describing events and towards the exploration and emancipation of human nature. This comparable shift can be seen in works of art as well, away from the Renaissance towards the Baroque, from religious, mythical and historical portrayals of human activity to a dive into a world of the unknown, the unexplained, the mysterious, the psychological. These are the paintings that are worth thousands of words as the content itself cannot be explained with a mere allusion or brief relation.

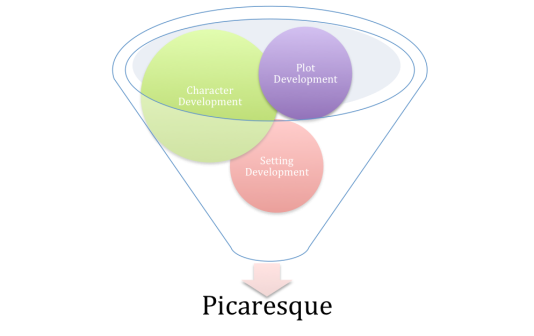

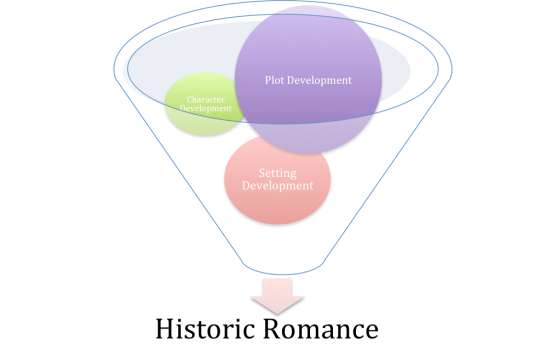

Likewise, La Celestina was no typical work of the Renaissance, not however, because it was a considerably ‘unholy’, even perverse creation that brought shades of gray to the previously defined categories of black and white. That is a shift in ideas, not a shift in style. What truly made the work a novel was that it combined the two essential ingredients to any successful novel, character and plot development, while laying it out as a narrative. The style itself speaks a lot of the genre that was to follow in consequent pioneering novels, the ‘Picaresque’, a style of writing popularized by Miguel de Cervantes in his famous ‘Don Quixote’. This was a challenge to the traditional and great teachers of morality, epistles and chronicles. All throughout the 17th century, we find that this style of writing has been heavily rivaled by a slight evolution, but no great enemy to Amadis of Gaul, early historical romances, popularized by authors such as Gauthier de Costes de La Calprenède, Madeleine de Scudery, and Honoré d’Urfé. The biggest difference between these two predominant genres was the degree of stylistic focus that has been placed on character or plot development.

As can be seen from the funnel diagrams above, generally, authors of picaresque novels have favored character development and those of historical romances have favored plot development. Mind you that all these novels had a complex narrative and prose, with dialogue being an important way by which the plot moved forward. They were true works of art, creations which could not be satisfied by one thousand pictures, either for their complex plot with sets of piquing troughs and crests, or for the dedication that went into the exploration of every corner of one sinful man’s life, with an express interest in depicting contemporary sociological impacts. Either way, these works, though highly under appreciated, unrecognized, unstudied, and nearly unknown to modern day readers, are the crux, the basis on which we rest the novel concept. Without them, Walter Scott, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Victor Hugo would never have been able to publish the works they did and our conception of literature would be completely different today. It is just as important to study early literature as it is to study early art. It helps us understand our own literature better and explore where we have progressed, regressed and where genre and style has merely branched off in an entirely different direction. As I go through the different stages of literature leading up to the modern era, I will reference specific authors more frequently and their works, and will attempt to give you a strong understanding of the changes and transitions that took place as writers began ‘shifting with the times’.

As can be seen from the funnel diagrams above, generally, authors of picaresque novels have favored character development and those of historical romances have favored plot development. Mind you that all these novels had a complex narrative and prose, with dialogue being an important way by which the plot moved forward. They were true works of art, creations which could not be satisfied by one thousand pictures, either for their complex plot with sets of piquing troughs and crests, or for the dedication that went into the exploration of every corner of one sinful man’s life, with an express interest in depicting contemporary sociological impacts. Either way, these works, though highly under appreciated, unrecognized, unstudied, and nearly unknown to modern day readers, are the crux, the basis on which we rest the novel concept. Without them, Walter Scott, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Victor Hugo would never have been able to publish the works they did and our conception of literature would be completely different today. It is just as important to study early literature as it is to study early art. It helps us understand our own literature better and explore where we have progressed, regressed and where genre and style has merely branched off in an entirely different direction. As I go through the different stages of literature leading up to the modern era, I will reference specific authors more frequently and their works, and will attempt to give you a strong understanding of the changes and transitions that took place as writers began ‘shifting with the times’.